A review of the new movie “Babygirl”

January 19th, 2025 by Roger Darlington

This is such a watchable film: glitzy (smart clothes, cutting-edge technology, pounding soundtrack) and erotic (solo sex, marital sex, transgressive sex). It is also such an interesting film, raising so many issues around relationships: age-inappropriateness, power and powerlessness, domination and submission.

I was struck by the number of young women at the screening I attended and I can understand why, since this is a movie that unusually adopts the female gaze and poses the kind of questions more usually in the minds of women: what is the role of fantasy in female desire? how acceptable is the orgasm gap? how does one move from faking it to making it?

Such a film could only be made by a woman and it comes – pardon the pun – from Dutch former actress Halina Reijn who wrote, directed and produced it. And the movie would only work with the right lead actors.

We are used to Nicole Kidman taking risks in her thespian roles and here she is simply wonderful as Romy, CEO of a high tech company who seemingly has it all in career and family terms. The revelation is Harris Dickinson (no jokes about his surname please) who is so convincing as Samuel, the young intern at the company who insists that Romy be his mentor. But who is teaching whom and who is consenting to what?

Throw in Antonio Banderas as Romy’s confused husband and Sophie Wilde as Romy’s ambitious aide and you have the perfect date movie. Just be ready for the conversations that follow.

Posted in Cultural issues | Comments (0)

A review of the 1955 classic “Rebel Without A Cause”

January 19th, 2025 by Roger Darlington

I confess that – other than clips on film courses – it took me 70 years finally to view this classic, but the delay meant that I caught it at the British Film Institute where I could view it in the original CinemaScope and Warnercolor. The work is famous as the third and last of the movies starring the charismatic James Dean who, at just 24, was dead by the time it was released.

In this coming-of-age movie, Dean plays Jim Stark, an angry young man full of teenage angst, searching for a sense of family. Early on, he cries out to his bickering parents: “You’re tearing me apart”. In the course of one day and night in Los Angeles, he has a knife fight outside the Griffith Observatory (much later to feature memorably in “La La Land”), he takes part in fatal ‘chickie run’, and he finds consolation of a sort with fellow high school students, Judy (Natalie Wood) and Plato (Sal Mineo).

Although the messaging is not exactly subtle (especially in these more sophisticated times), the film is a triumph for Nicholas Ray who both originated the story and directed.

Posted in Cultural issues | Comments (0)

When and where was the world’s first railway line?

January 18th, 2025 by Roger Darlington

The world’s first public railway to use steam locomotives ran between Stockton and Darlington in the north-east of England. Since my family name is Darlington (although I’ve only visited the town once – in 1983), this historical event has always had a special resonance for me.

The line was officially opened on 27 September 1825. Of course, that means that this autumn will see the 200th anniversary of the event. I’m sure that locally there will be some celebrations and it may even make the national and international news. Remember where you heard it first.

The Stockton & Darlington Railway Company operated until 1863, but much of the original route is still used today by the Tees Valley Line operated by Northern.

You can learn more about this historic development here.

Posted in British current affairs, History, My life & thoughts | Comments (0)

Which British politician was responsible for the introduction of the world’s first zebra crossing?

January 12th, 2025 by Roger Darlington

The answer might surprise you – as it did me when the question was recently put to me by a friend over dinner. The answer is Jim Callaghan who, at the time, was a junior minister in the Ministry of Transport in Clement Attlee’s postwar Labour Government and subsequently became Prime Minister himself.

In 1948, Callaghan’s ministerial portfolio included road safety and, in that capacity, he visited Britain’s Transport and Road Research Laboratory where he discussed and supported two new safety measures: the zebra crossing and illuminated metal studs (known as ‘cat’s eyes’). The first zebra crossing was then introduced at Slough High Street on 31 October 1951.

The story is that, on his visit to the laboratory, Callaghan remarked that the new black and white design for a pedestrian crossing resembled a zebra which led to the popular name for the innovation, but he himself never claimed authorship of the term.

Fast forward to 24 March 1972 when I was invited to the House of Commons to be interviewed for the award of a Political Fellowship offered by the Joseph Rowntree Social Services Trust. The interview panel was headed by Jim Callaghan and I was given the fellowship, initially working for him and then for Merlyn Rees.

Jump again to the spring of 1976: Harold Wilson resigns as Prime Minister, Jim Callaghan runs to succeed him, Merlyn Rees becomes campaign manager for Callaghan, I attend all the campaign meetings, Jim wins the election to be party leader and therefore PM and he invites me to run his political office at 10 Downing Street.

In fact, private funding for the political office was not forthcoming, I never moved No 10, and instead I continued working as Special Adviser to Merlyn until 1978.

Posted in History, My life & thoughts | Comments (0)

Normal service will now be resumed

January 6th, 2025 by Roger Darlington

I’ve had a personal blog called NightHawk for 22 years now but, for the last three weeks, I’ve had a technical problem which has prevented me from blogging. This has been one of the longest down times in the life of my blog and it has been deeply frustrating.

But, thanks to an IT wizard, the problem has now been resolved and I can resume my blogging. Thanks, Luke!

Posted in Internet, My life & thoughts | Comments (0)

A review of the new Indian film “All We Imagine As Light”

December 14th, 2024 by Roger Darlington

When we think of contemporary Indian cinema, we usually have in mind Bollywood movies with singing, dancing, action, romance. “All We Imagine As Light”, both written and directed by Payal Kapadia, could not be more different: it is an art house film that won the Grand Prix at Cannes in 2024. Much of the film is actually set in the home of Bollywood, Mumbai, but this is not ‘the city of dreams’, rather ‘the city of illusions’ and indeed disillusions.

There are 21 million stories in Mumba, but this is simply those of three characters who all work at the same hospital: the nurse Prabha (Kani Kusruti), her younger colleague Anu (Divya Prabha), and an older cook Parvaty (Chhaya Kadam).

Like any art house work, there is very little plot or action but a slow exposition of character and emotion. It is a film about friendship, more specifically about female friendship, even more particularly about the impact of different forms of patriarchy on these women and their friendship. Again like most art house films, some of it is opaque, even mystifying, particularly in the interaction between the nurse and a man whose life she saves.

It is difficult to make art house films in India and the funding for this one comes from a variety of European sources including France, Luxembourg and The Netherlands. Some in India itself have challenged the work as not so much an Indian film as an European art house film set in India. Whichever way you look at it, this is a rare work that is much to be admired and enjoyed.

Posted in Cultural issues | Comments (0)

A review of the bestselling novel “Conclave” by Robert Harris

December 13th, 2024 by Roger Darlington

Harris is one of the best-selling authors of British fiction and has made his reputation with a series of works usually set in a particular time and/or place and drawing on much historical research. He is not a great writer and often the journey is more interesting than the destination (his endings can be weak), but he is a consummate storyteller who is consistently entertaining and informative which makes his books real page-turners. “Conclave” is the ninth novel of his that I have read and, while it was published in 2016, I did not read it until encouraged to do so by my admiration for the 2024 film adaptation.

The word conclave comes from the Latin con clavis ‘with a key’ and, in this case refers to the sequestration of the College of Cardinals of the Catholic Church when, as has been the case since the 13th century, they are confined to the Sistine Chapel of the Vatican to vote for a new Pope. It is a concentration of a few powerful people – in this case 118 holy (maybe) men (certainly) – who, in a succession of ballots over a just a few days, select the leader of 1.4 billion souls.

It turns out that the film is a very faithful version of the novel, even down to actual lines of dialogue. The only significant difference in the two formats is that, while in the book the central character is an Italian Cardinal, in the film he is British which enables the casting of the wonderful Ralph Fiennes. Where the novel scores is in its detail of the Vatican buildings and historical references to previous papacies, but I was more impressed by the movie because of the fine acting, splendid cinematography, and evocative sound.

Posted in Cultural issues | Comments (0)

What was most popular on Wikipedia in 2024?

December 5th, 2024 by Roger Darlington

Seventeen years ago, I wrote a column with the title “Is Wikipedia the best site on the web?”. I thought then – and I think now – that it is an amazing resource and I use it every day. It is totally non-commercial and funded by subscriptions. I’ve long donated annually and fore the last few years I’ve donated monthly.

The metric of its success are astonishing. 986 million unique devices per month in English. 2.4 billion hours of reading in English. 300+ languages and counting. 4.5 billion hours reading in all languages.

As 2024 comes to an end, these have been the most visited pages on Wikipedia in the past year:

- Deaths in 2024, 44,440,344 page views

- Kamala Harris, 28,960,278

- 2024 United States presidential election, 27,910,346

- Lyle and Erik Menendez, 26,126,811

- Donald Trump, 25,293,855

- Indian Premier League, 24,560,689

- JD Vance, 23,303,160

- Deadpool & Wolverine, 22,362,102

- Project 2025, 19,741,623

- 2024 Indian general election, 18,149,666

- Taylor Swift, 17,089,827

- ChatGPT, 16,595,350

- 2020 United States presidential election, 16,351,730

- 2024 Summer Olympics, 16,061,381

- UEFA Euro 2024, 15,680,913

- United States, 15,657,243

- Elon Musk, 15,535,053

- Kalki 2898 AD, 14,588,383

- Joe Biden, 14,536,522

- Cristiano Ronaldo, 13,698,372

- Griselda Blanco, 13,491,792

- Sean Combs, 13,112,437

- Dune: Part Two, 12,788,834

- Robert F. Kennedy Jr., 12,375,410

- Liam Payne, 12,087,141

Posted in Internet | Comments (0)

A review of the entertaining new film “Conclave”

December 2nd, 2024 by Roger Darlington

Which is best? The book or the film? It’s an endless – and perhaps fruitless – debate.

I’ve read and enjoyed so many books by Robert Harris, but not the 2016 novel on which this film is based. The book has been an international bestseller, but this excellent cinematic version has so many visual and aural elements that cannot be rendered as vividly on the written page: imposing settings in Rome and at the Cinecittà Studios (standing in for the Vatican), vibrant clothing and ornamentation (all that red and all those crosses), superb cinematography (the French Stéphane Fontaine), an arresting soundtrack (the German Volker Bertelman), a magnificent roster of actors (Ralph Fiennes, Stanley Tucci, John Lithgow, Isabella Rossellini), and lines delivered in Italian, Spanish and Latin as well as sonorous English).

Of course, we have to thank Harris for the narrative: the machinations and power plays of the election of a new pope by the College of Cardinals sequestered in the Sistine Chapel. However, German director Edward Berger, giving us such a different work from his “All Quiet On The Western Front”, and British scriptwriter, Peter Straughan, who adapted “Wolf Hall” for television, have done brilliantly in creating a cinematic version, while Ralph Fiennes – playing the cardinal who must convene the conclave – gives an understated, but career-best and Oscar-worthy, performance.

If the film has some weaknesses, they are essentially those of the novel: a rather fanciful plot with a weak ending and a simplistic representation of the dichotomy in the Catholic Church of the debate between liberalism and conservatism. But now I am going to read the book …

Posted in Cultural issues | Comments (0)

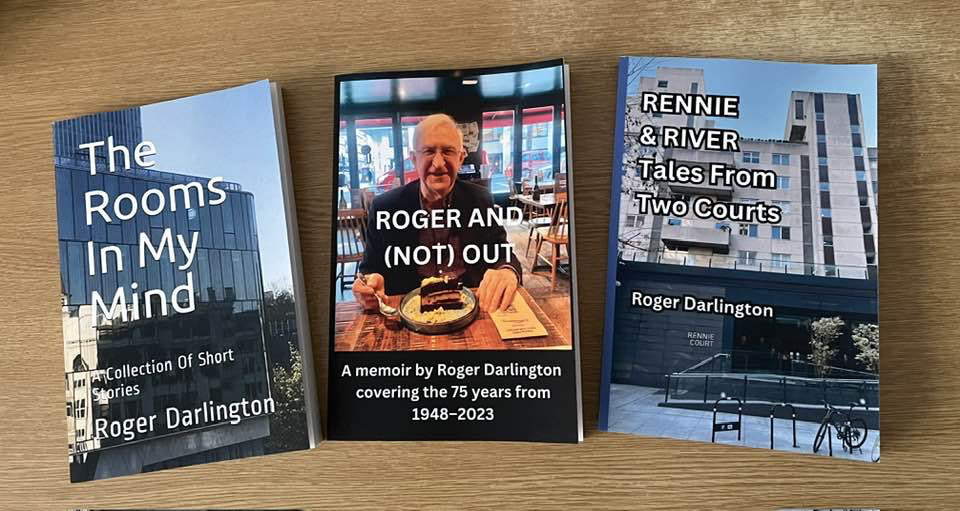

Need a suggestion for a Christmas present?

December 2nd, 2024 by Roger Darlington

This Christmas, if you’re looking for a modestly-priced and personal gift for family and friends, please consider one of these books which are available on Amazon. You can tell them that you know the author.

Posted in My life & thoughts | Comments (0)